-- Story of a Black Prisoner

at a Nazi Labor Camp, 1943-1945

By Ivan D. Alexander

1. Giammai's Notebook

They say that even truly crazy people believe themselves to be sane. Actually it was my friend Giammai who said this. If those years at the camp made us crazy, we did not know it.

I knew him when we were at the camps. His real name was Jeremiah, but everyone knew him as Giammai. He first said he was Egyptian, or Ethiopian, but at other times he said his father was American, that they lived in Paris before the war, and his mother was from Sicily. I believe this was true. At another time his mother was an African princess, his father a handsome Sicilian sailor. He was once even Algerian. He spoke several languages and was educated in a manner of speaking, he knew a lot. His skin was the color of dark cafe au lait, but the Germans called him "schwarznegger". I never knew really who his parents were, since the stories changed from time to time. But I knew Giammai, and he was a modest and most unusual man. In fact, I think he was the most unusual man I had ever known.

I now live in the suburbs of Paris with my husband and children. Those strange days of long ago seem like dull memories to me, perhaps I had tried so hard to forget them, perhaps because I was dulled then of my human senses and had to regain them one by one over the years to once again be a human being. I kept Giammai's notebook, that thick and soiled notebook he kept hidden beneath the grey bare mattress in his barrack. It still smells of sweat and the fetid air, the smell of humanity doomed to hell. And in its last pages over old dried stains of blood he wrote his last testament. It remains unfinished... But when I put it in my hands, I always turn to the page that is my favorite, the one that truly reveals to me the man's soul. On it is written in his tiny hand, for he needed to say much on each page, the words forever etched into my memory.

"I dreamt this morning that I was in the Garden of Eden. All the plants, so green, were nodding to me with each passing breeze, as if they knew me and spoke. It was not each plant by itself who knew me, but all of them together as if they were one organism that warmed at the sight of me, and I warmed at the sight of them. They liked me."

What powerful memories this brings back to me. My eyes tear even now as I write this. But I will be faithful to what he had written and what I knew of him in those terrible days of the holocaust. The story I am about to tell is of a world that was darkly shut off from all the things that are beautiful in the world, that makes each human being so very special, with joy and laughter, with ideas and dreams, with hope. It was a time when those who were doomed knew they lived only for today, for tomorrow they, like their families and friends, would be dead. That I survived compels me to tell this story that must be told.

* * * * * *

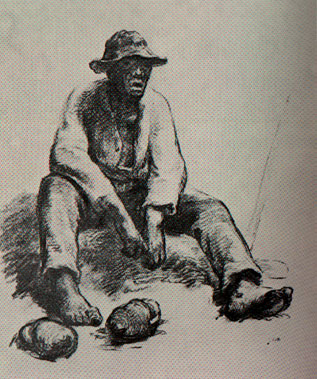

I loved him in my own way. My eyes first spotted him amongst the other prisoners dressed in the drab grey striped camp uniforms as he picked through the piles of clothing and valises left behind by the teeming mass of humanity that had been brutally marched off barefoot to the delousing chemical baths. It was not because he was dark skinned, and I had never seen a dark man before, but it was because of the way he moved. Amidst all the shouting and shoving and whistles of loud violence he moved slowly like a sage of the netherworld into which we had all fallen. His movements were strangely choreographed as his hands reached for the colorful remnants of what had been adornment for those no longer here. As he worked, his eyes turned to me and, after a long pause that spoke of thoughts confusedly fleeting like apparitions just before waking, he smiled. In that cold grey dawn, he smiled at me. It was a cavernous smile, his hollow eyes sunken in dark hollow cheeks, yet it nevertheless lit up his face into a human smile. The other prisoners doing like work did not notice him, nor me, and kept their slow pace as if we did not exist for them. In their minds, no doubt, we already did not. But in his eyes, I existed, and so though wretched I was after such a long and arduous train journey, hungry and thirsty, I smiled at him too.

My journey to the camps started when the Nazi soldiers sent my university director a list of those who were to be transported for labor. My name was on that list, though I did nothing to earn this. There were others who had consorted with the partisans, or who had run away from compulsory searches, or who had been denounced. But I was none of these. As my heart sank, we were all standing in the chill school yard under heavy clouds, my mind frantically tried to reconstruct why they had chosen me. True, I liked a boy who later ran off with the partisans. He had said he was against the Russian Communists and wanted to fight them. I did not really understand why he felt this way, for the Communists were there to bring us a better world. In Ukraine there were many who felt this way, but we were Swedes by blood, so did not take much part in all of the people's sentiments about the war. My father was a country doctor in our home town, and he always said, before being sent to work in Siberia, that all these terrible things were to pass, and to not become embroiled in their politics. Our Father Stalin was a good man, and would look after all of us. But I was innocent, and had no cause to be called. It was then the beginning of my journey, and the long and cold and difficult train full of crushed souls who cried silently in the dark, that brought me to this unloading station in the camp. I was not even sure where I was, and frightened, since for some reason I was not sent to the baths, but kept aside by the officers who selected us. In that smile was the first human touch I felt since I was taken from home.

"Kostia." That was his first word to me. He spoke passably good Polish, which I understood. "I will call you Kostia." But my name is..." I was about to protest when the Slavic guard gave us both a hard and dark look, his hand reaching for his wooden club, and we both turned away from each other. The Germans did not use their own to guard the prisoners, having their hands full at the front, so they used guards of all the undermensch nationalities for their police work. Mostly they were Slavic peoples, Czechs, Russians, Poles, Ukrainians, Lithuanians. All did their dismal work without feeling, though I believed some enjoyed it. But Kostia was to become my name at the camps.

I was standing there with the other women who had been chosen. It was hazy sunshine, though still cool. There were a dozen of us, all sad and weak with hunger, exhausted. We were all pretty women, despite our sad condition, and the German officers of the camp selected us personally. They made us understand we were to be household staff, that we were lucky not to be sent to the factories and farms like the other workers. We were not called prisoners, but workers. The head officer's interpreter was a prisoner, and he haltingly translated his words into some semblance of a mixture of Slavic dialects. But we understood, even if he had said nothing. We were chosen for something else, we were lucky, and now were left standing there, alone and weary of our fate.

We women were looking at the small pile of children's shoes that had not yet been taken away. Some were fine shoes, so that they stood out from the rest, of red or blue leather, comfortable, secure around the little feet they covered. The grey prisoners had removed the valises and now were scooping up the last of the shoes with shovels, to be carted away in wheel barrows. The families were told they would get them back later, distributed to everyone. But would they ever see them again? The ground was still muddy from the morning rain, and the shoes on the bottom were wet. I did not see the children now, after the initial tumult when herded off the trains. I wondered if they were too frightened to feel the cold ground on their bare feet. Were they Jewish? Or non-Jewish? They too were captives of a fate not of their choosing, lost in the confusion of this insane war. Like their clothing and shoes, discarded lives in a crazy world.

The young woman next to me had the courage to speak. She barely whispered, and did not look at me, but I knew she wanted my attention.

"My name is Tania? I am from Romania."

I did not answer immediately, but quickly looked around to see if the guards had heard. None motioned to us, so I whispered in answer.

"My name is Olgha. I am from Romni. But I live in Lviv now."

She looked up at me shyly and let a trace of a smile cross her lovely face. I think she, like me, found it funny that we came from different places that sounded alike. She was dark, dark eyes, dark hair, even her complexion was more swarthy than mine. Perhaps she had worked outdoors, but she was young and pretty to look at. I felt very white next to her.

Just then the officer, which we guessed was one of the camp's commandants, for he looked important, returned with two orderlies by his side, barking instructions at them.

The commandant was a small man, not taller than us women, sallow faced with small dark hollow eyes, looking serious beneath his officer's cap. In his grey SS uniform, he did not strike a gallant pose, as some men do. Rather, he looked soft and paunchy, which would have us women laugh, were he not so severe in the way he looked at us. However, the swastika and medals and braids on his lapels told us he was an important man. The man swaggered over to us. I had seen men like this before, and in their smallness they make themselves big, which I feared. We stared at him in sullen silence. He motioned one of the prisoners to translate for us.

"Meine Shatse!" he began. The prisoner immediately took over.

"His commandant, who is the law of this camp, says you are not to be afraid. You will be fed and taken care of, as long as you do as you are told. Be obedient and attentive in all the things demanded of you, and no harm will come to you. Disobey, and you will be punished severely. We do not tolerate speaking until you are spoken to. You must obey the guards, for they are here to protect you. Anyone caught doing other than allowed will be beaten. Obey, and you will be rewarded with warm food and comfortable clothes."

He looked around at us to see if we understood. Our eyes no doubt told him of the fear he was evoking, which made him glad. The translator continued as the commandant spoke, now more agitatedly.

"I have not had any disrespect in all my tenure here, and no one has dared to lift a finger against the guards. Anyone who tries, I warn you now, will not live to the end of the war. But if you are good workers, then you will be liberated when our glorious Fatherland has conquered all the inferior nations."

Now he was steaming beneath his cap and small beads of sweat began forming on his forehead, so he took off the cap pulled down severely over his brow. He was bald, with only a few thinning hairs pomaded down. We stared at him, when one of the women broke out into a light laughter. But she immediately stopped, realizing what she had done.

This froze the commandant. He stared over at her, put back his cap, and took three long paces towards her. There he stopped, looked her in the eye as if to challenge combat, and with his gloved hand struck her hard, once, and then once again.

The young woman, a pretty woman, skinny but with well defined lines, curly blond hair, blue eyes, flushed instantly from the affront. She had meant nothing, no more than the rest of us, that here was a small ludicrously insignificant man exuding such great power of self importance. But none of us laughed, for now we were shocked.

The commandant motioned to one of the yellow green uniformed guards, who immediately stepped up to him, and without salute, as we would have expected, began beating the woman with his fist. Then he dragged her away from us and lifted his club, and there beat her until she fell to the wet ground, barely conscious. Then the guard, a youth of perhaps no more than eighteen, in his last gasp of rage, for now he was getting out of breath, dragged the young woman back to the others and left her there.

The commandant then dismissed him, and the guard stepped back a few paces, his face still red from the strain of the beating. The young woman, we later learned her name was Lyuba, began coming to again, her face swollen and bloody, short of breath, moaning quietly. Then she broke into tears and cried softly to herself. The commandant resumed his command.

"Get up woman! You will not insult me again. And for you will be the hardest work in the kitchen, the hardest. You will clean latrines with the other prisoners until you are fit to serve me. Look at yourself! A shame! Look what you have done! And next time I will not be so easy."

Then looking around at the rest of us, who were now stooped in submission, our eyes avoiding his gaze, he pronounced.

"You will now be marched to your barracks, which are adjacent to the kitchen, and take showers to clean yourself of the filth you brought with you. I will not have smelly women serving in our officers's personal quarters."

With that, the small man wheeled and marched off, followed by his adjutant and orderly. The guards then barked an order at us to fall into formation, which did not mean much for we did not know what formation meant, but we were mindful of their clubs, and thus we marched off as we were told.

* * *

I looked into Giammai's journal again, to find the other page that always called to me, so much of him.

"I have looked into the eyes of God, and now I am cursed, for I can see what other humans cannot, that we are the damned, and this is a terrible burden on me."

2. The New Woman

The bolts shot back and doors rattled open. The train had just arrived in the grey early morning and ground to a halt. The German soldiers, one for every four Ukrainian and Polish prison guards, immediately began barking orders at the confused human cargo peering out into the daylight from inside the dark wagons. Mothers clutched children, men trying to look brave, but on all faces were fear. The German shepherd dogs barked, held by the chains in German hands. I was resigned to another day of unloading the trains, as were my fellow prisoners, knowing that the fate for this God forsaken cargo was sealed in some papers issued from Berlin. They were to be marked, tagged with tattoos, if they were lucky, and put to work at the prison factories and cultivation farms. If unlucky, they would be sent off within a day or two to die. Though it was not always like this. At the beginning of the war, this was even considered a model labor camp. Of course, it was opened for political prisoners, though who did not agree with the Reich, or simply did not fit in with it. But as the war progressed, things got prgressively worse.

Such was the day that I faced when I laid eyes on an attractive young woman amongst the passengers. She was in the women's car, and for them was a more sinister destiny. They would be put into the camp commandant's care.

" Los Schnell! Schnell!" The Germans yelled at them as they were being forced out the wagons that only days ago they were forced into. I knew they had ridden without food or water standing up, dirty, tired, afraid. I had done the same from France. Now we were in the heart of Germany, all thrown together from East and West, into that Aryan melting pot of the Third Reich, from which only a few would survive. This was decreed by God, and no man could undo what had been ordained for them. Whether God or Satan, none could tell.

The Slavic prison guards jockeyed for position to have the best shot at hitting the new arrivals, as if to show their German masters that they were good obedient dogs. They also competed against themselves, Poles against Russians, Ukrainians against Poles, Russians against Lithuanians, for they all secretly hated each other, each poisoned by their own putrefying nationalism, same as the Germans uniformly hated all of them. So theirs was a task to please their hateful masters with increased cruelty, so no one would be singled out as a slacker in this great cause of the Aryan race, a cause to which they too were doomed. As the prisoners hesitantly jumped down on weak legs from the meter high wagon floor, they were met with shouts and blows to their bodies, quickly separating men from women and children. Children cried, as did some of the women, and some of the men. It was a fearful sight to see grown human beings emasculated of their humanity before their children's' eyes. What were the children thinking as they saw this? If they survived, would they ever be normal adults? But I could not think of these things at length, or the blows would come my way if I slowed my pace of moving the human bodies towards their destined spots. There, they were ordered to leave on a pile their belongings, keep their coats, but cast off their shoes and unnecessary clothes. This made no sense, since the ground was still cold from the overnight rain, but then sensibility was not the norm here. It was to obey orders barked by the human captors and their dogs.

She jumped down from her wagon with only a small valise in her hand, which she tossed over to the pile and assembled with the other women who were directed to be together. Her hair was a long blond, her skin like snow with a touch of flushed color to her cheeks and lips, and she walked without a sign of fear in her blue eyes. I knew she was afraid, but she chose not to show it, a mark of a strong woman. From this group were taken some to go with the other women and children, leaving behind only the best looking ones, the selection proceeding through elimination of those less comely. I knew because every month the same selection took place, only a dozen or so would be taken from the hundreds. She was alone, not waving to any of the departing men. When the wagons were empty, the men were herded away in one direction towards the men's barracks, and the women and children towards another. Soon they were beyond the gates and barbed fences of the train staging area, pursued by barking and shouting, catching blows, on their way to see the "doctors", and then the "decontamination" yard. I was ordered to load up the valises into the wheel barrows manned by other prisoners. But this brought me closer to the woman I caught briefly in my eye. When I had gotten close enough, while the other women chosen were standing quietly together, as she looked over at me, I spoke to her.

"Kostia, your name will be Kostia."

She looked over at me, and I tried a smile, which was not easy, for fear was thick in the air. She half smiled back, puzzled, but looking at me. She was about to speak when the guard looked over at us threateningly, so I quickly let go her eyes.

She had fine eyes, intelligent, set in a fine face with high cheek bones, which is why the name "Kostia" came to me. It was one of those names that materialized out of the ether, as if whispered by an angel, not bony but fine boned. She was angelic in one sense, but also regal in another. If I had met her on some ancient battlefield, I would have dropped my bow and arrow and let her pierce me with hers. Perhaps it happened some long ago, but we cannot know such things. That she came into the camp is what happened, no more, no less, and that I am here is the same, no more.

The camp commandant, whom we called "Shwarz", a good name because he was a small dark man, had approached the women and began lecturing them. We prisoners knew the story well, obey or be punished, or killed. He then proceeded to demonstrate his sincerity by having one of the women beaten. I and the others were called away, to bring the last of the belongings into the sorting barracks, where most things would be confiscated for the Fatherland. The shoes would be repaired in the shoe factory, with wooden shoes given to the prisoners in exchange. What will be returned will be laid out on long tables, glasses, photographs, useless documents, with each prisoner given five minutes to identity what is his or hers, and then they would never see their things again. Unclaimed items go to the war effort. Nothing would go to waste.

The men had already been herded to their men's barracks, the women and children still undergoing humiliation, standing naked and barefoot in flea baths, the chemicals stinging them, hurting their eyes, children crying. This was the efficiency of the German machine in action, so that fleas and lice would not be spread in the barracks, but it did not work. There were more inside the barracks, which we could never kill, and learned to live with. In fact, we envied them, since they ate better than we. Prisoners were thin, surviving on one piece of coarse bread and a thin turnip or cabbage soup, with potatoes if lucky. The fleas had real protein from our blood. We joked they were German fleas, since they were so fat, as if fattened on sauerbrotten and sausages. They gave us coffee in the morning, but it was so diluted we called it pissenwasser. Tobacco was only available when the guards threw down their butts. Once we got jam, when the Red Cross people came by, but that was only once. In fact, we were hungry all the time.

I had not seen Kostia for a very long time, maybe six weeks, for we traveled in different groups within the large barracks compound. We I saw her again, she looked well, but thinner. We briefly exchanged glances, and then recognition, and then found a way to signal each other that we needed to talk. She still had her hair long under her camp kerchief, unlike the other women whose heads had been shorn.

"I need your help," she said urgently to me. "I..." Kostia quickly looked around to see if it were safe to talk. Her survival instincts had already awakened, as it did for all who wanted to survive. Determined it was safe she continued. "I need you to pass a message to Renato, an Italian in the men's camp. His wife, Livia, is desperate to see him, to talk to him. They are deeply in love, and she misses him terribly."

"It is a wretched fact of life here, loved ones separated, husbands from wife, children from their parents."

"She says she will die if she cannot tell him she loves him."

I understood, and knew how to reach the man, and said so.

"Tell her to wander near the fence towards the men's camp, just before afternoon roll call. And tell her not to throw anything to him, or they will punish them both... or kill them."

Kostia said she knew about this, that to give anything across the fence, a cigarette, a piece of bread, or God forbid a potato, even a note, was punishable severely.

We had a few moments together, so we quickly exchanged news. Kostia was working at the officer's mess as a servant, and as a kitchen helper. The other women were there too, except for the woman who was beaten, Lyuba, who had been further beaten, because she had a facial expression of mirth when she should not have. Kostia said it was in her nature, a gentle woman, but who could not help herself, for when she grimmaced under the most bitter circumstances, it looked like she smiled. So she was beaten until she could not walk, and then sent to the "clinic" for rest. The last she heard of her, she had been put to work in the fields outside the camps where they grew potatoes. This was very hard work, because the prisoners had to walk many kilometers to get there, and then, when totally exhausted and hungry, they had to walk back.

"The capo woman is very severe with us," she said after telling me the other things.

"Do they bother you, the men?"

"They like to tease us and touch our privates when we are near them, serving them at table, but they have not hurt us otherwise." She stopped and thought a moment. "I feel like they are watching us all the time, like we are kept animals fattened for eventual slaughter."

We both laughed a little at her wording, since fattened was not at all true to the camps. Rather, we were being starved for slaughter.

"And of the other women?" I had only this question, because I had to make ready to return to the laundry barracks where I was working, only here at the officer's mess to deliver clean linens. Our clothes were grey and dirty by comparison, so it made a stark contrast to carry the white folded linens, but there was little time to reflect on this. Then we could hear footsteps, and Kostia immediately turned away from me and disappeared into the door that led to the kitchen. We did not see each other again for another week.

There was a new thinness in Kostia, her eyes were taking on the hollow sorrow all us camp prisoners carried. It was from crying, from being eternally depressed, from being beaten or fearful of being beaten. The Slavic guards always looked for an excuse to beat us, because this elevated them in the eyes of the SS command. The commandant, Shwarz, would even publicly praise a guard for having given a good beating. When they beat us, they foamed at the mouth, they worked so hard.

The Germans loved their dogs in ways that seemed out of place in this horrible place. I watched an SS officer speak affectionately to his dog, pat it on the head, give it a morsel of food, while only moments later he had his whip out against a prisoner who had spilled some soup he was carrying, raining blows on this poor man who dared not cry out in pain. The dog was held back, but could not wait to tear into the unlucky fellow. It is so maddening to see officers swagger with their little whips, more like riding crops, tucked under their arms, pistol holstered and well oiled. But there is nothing we can do, but obey. Always "shnell!" Obey quickly, or you will be beaten. Some even laughed that the workers should be beaten when they get up and before going to sleep so they will not forget where they are, and so they will never think of disobedience. Such is the mind of the Aryans, that they must be obeyed all the time, and quickly.

I returned to the laundry with the soiled linens, which had sauces and wine stains. It was as if I were carrying the shrouds of pigs which had left their filthy saliva on them. The other prisoners then set to the task of boiling the linens, and to wash them with the caustic soap of the Third Reich which turned their hands red, and made their eyes smart. What these devils put in that soap we could not guess, unless it was the poison of their great leader, their Fuhrer, whose poison coming from his mouth infected all the things that were theirs. They are a poisoned race, not the superior race. This is the poison all of us had to eat everyday of our lives, until we sickened, and died.

I sent word through our camp network to find Renato. There were quite a few Italians, but there were more spies, so we had to be careful how we asked. If found out that a secret message was being passed, this could be taken as a grievous offence against the Reich, punishable by death. Death was merciful if a pistol shot to the head, but less so if starvation and dehydration, and ultimately hanging by the arms tied behind one's back, so to die slowly and in great pain. We were not human beings here, for we had fallen into the lair of the devil. I do not believe in the devil, so I had fallen into that horrible hole where one's soul is tested and tortured, at the hands of men. The devil is us.

Capos are the biggest devils, because they turn on their own. But as it is Christian to forgive, even the Jews must forgive, for the capos are only doing what they can to survive themselves. A good capo will assign you to an easy day's work if you are ill or hurt from beatings. An evil capo will make sure your suffering is doubled, so that perhaps you will not survive. If you are too weak to work, the capo can send you to one of the extermination camps. And yet, the prisoners forgave them, avoided them, begged them, kowtowed to them, anything to live a little longer, with a little less suffering.

But I had a capo friend who had managed to fool the Germans into thinking he was a cruel task master, when in fact he was not. This took great cleverness on his part. His name was Jan, a Pole.

"I have found the Italian you are looking for, but he is about to be transported to a death camp," were his solemn words. We both knew that his days on Earth were few, and my heart sank thinking of the poor woman who was searching for him. He told me where to find him. I went there on pretense of going to pick up soiled laundry from the guards.

"Giammai, be cautious," was his only other words to me.

"Is there laundry?" I asked of the first prisoner I saw, who was sweeping the parade ground.

"The guards have left a pile for you over there," he pointed to their building.

"I need to speak to Renato, special message from his barracks capo."

"He is at the shoe factory behind that barrack there," he pointed again. Then as if I had never asked him anything, he began his sweeping again, which was painful to watch, since he moved with obvious pain with each brush of the broom.

I found Renato hunched over his machine, hammer and nails in hand, working amidst the din of the factory. I came over to him, still carrying the bundle of soiled laundry, as if coming to collect more. When I was close to him, without looking at him, I whispered the instructions so that he could see his wife. Then I turned slowly and moved away from him. His face looked up at me, but I could not return the look, if we were to not arouse suspicion. The capo in charge of his section had his back to us, so we were not spotted.

That night, back in our dirty lice ridden barracks, under my thin foul blanket, I pulled out my little notebook from under the straw filled bedding where it lay hidden. In it, by the passing searchlights which shone through our grimy windows, I wrote the following memory to myself.

"I do not believe in the devil. The devil is a black beast like me. But he is kind next to these beasts who imprison us here. The real evil, black or white, is he who has a right to beat you, and torture you, and take away your life. The real devil is a man with a gun."

I put back my notebook into its hiding place, along with the dull pencil I sharpened with my fingernails. Then I lay back on the foul mattress and pulled the cover over myself, for the night was cold. I could hear the rain and wind outside. Around me lay exhausted men, some coughing, others moaning as they moved. The sound of snoring soon took over these sounds, and I too lay close to sleep, exhausted to where my body was no longer mine. Hunger lay in the pit of my stomach, but this I had gotten used to. Somewhere on my body I was being bit. It did not matter. Nothing mattered anymore.

3. The Meeting

When I found Livia, just before roll call, I quickly passed the words given to me by Giammai. It took some effort, since my Italian was minimal, as was her German. When she understood, she suddenly lost her pallor, her crushed sadness lifted by color returning to her cheeks, and she came alive before my eyes.

"Oh, God Bless you! You are a heavenly angel sent to me."

"Not an angel, Livia, only another sad woman like you." We both wanted to hug each other, but there was no time, for roll call would be in a short while.

We prisoners were given a few minutes to linger about the parade grounds before attendance was taken, where we were made to stand at attention for an hour or two, depending upon what the guards and SS had in mind. It did not matter the conditions of the weather, or whether or not you were ill. You had to stand at attention. If you fainted from hunger or weakness, you were taken away and punished. But we had a few minutes to linger, and this was an incredible freedom for us, to linger on our own.

They soon came from all directions of the camp, from the factories, from the fields outside the camp, from the latrines, all moving slowly like living corpses. The parade ground became a human sea of drab grey striped pajamas as they moved about like a large herd of sick human cattle. Livia was amongst them, with her daughter, one about sixteen, the other woman next to her was a childhood friend. They had met up at the camp, unbeknownst to the other that they had been taken prisoners. I watched as they slowly made their way towards the women's side of the fence where separated by two layers of barbed fencing was the men's side. Roll call was about to begin, and orders would be barked by the capos to fall into formation, and to stand at attention. Just then Livia saw Renato.

"Renato!" she yelled over to the men's side. It was like the voice of a wounded animal.

"Livia!" shouted back her husband. All had turned to look at them, for this was forbidden, to shout like this in the parade grounds.

"I love you Renato, I love you. Ti amo!" Her daughter also. "Ti amo Papa!"

"Ti amo, tesori miei! Ti amo Livia, mia moglie. Ti amo Gemma!"

Tears were forming in eyes who were closest to me, as they were in my eyes, but fear made me stop them, same as fear made the others stop theirs. It was not to be to let oneself fall back into feelings of love, of being a normal person with any feelings, not here. Perhaps not ever.

They looked at each other through the distant fences, sending kisses from their lips through their hands, when the capos rounded up the women and with blows of their clubs sent them away from there, bellowing at them to stand at attention while they hit them. The same happened on the other side, poor Renato beaten about the head by a guard. Shouting was allowed by the guards.

This meeting was relived like this for a few more days, though without them shouting their messages of love, they instead looking at each other from a distance, in silence, letting their eyes speak for them, or jesticulating with their hands. The other prisoners no longer noticed them, and even the capos ignored them. But the day came when Renato was no longer there, and Livia and her daughter were heart broken into a stunned silence. When I was with them again for roll call, I could not get two words out of them. They fell into a deep dejected silence, so that even when we stood together, it was like standing next to an upright corpse. Yet I was helpless, for I had done what I could, to at least say goodbye to each other. In the camps tomorrow never comes, with dreams and hopes and human feelings. Instead it is a perpetual hell of today.

We worked hard at our labors. Though those of us who were of the officer's mess staff worked under less grueling conditions, we nevertheless had the same hunger and exhaustion. But with our labor came a special humiliation. Our hours were long, fourteen hours or more, and our meals were not much better than for the other prisoners with whom we ate, though the cook might slip us a boiled potato if no one was watching. There was a great risk in this, for the cook, who also was a prisoner, and for us. What made it more painful was that we were degraded even further as individual human beings. In the officers's eyes, we were their playthings.

"Oh, come on Liebshun! Give me a little more beer, and warm it with your nice ass for me!"

They would stare at us, tell rude jokes which most of us did not understand, not being fluent in German, and had to silently endure their touching. We were not women who were proud of their womanness, but rather became ashamed of it.

It had been a long time since I tried to look at my face in a mirror. There was no point in it. My cheeks had gotten hollow, my lips lost their natural color, and my eyes, though still blue, had a new vacant look to them. When I did come across a mirror, I tried not to look into it. Once I found a small piece of a broken mirror which had been discarded by someone in the officers's quarters. I picked it up, and secretly found a place to look at myself. From that small sliver I could see my figure had narrowed, my breasts no longer womanly, and even my neck had become thin. I suffered from hunger like everyone, especially since it was my duty to serve the well fed SS men, those men who should have been at the front fighting for their glorious Fatherland, for their Fuhrer. Instead, their bravery was paraded in how well they beat the poor wretches who were trapped inside their grasp, who were surrounded by fences and machine guns, who endured their insults and blows silently, until they either stopped feeling them, or they died. I put back the broken mirror where I found it, resigned to the fact that it told the truth, and that I lived in a world that was a perpetual lie. I could not endure the truth anymore.

The commandant one day called all us women into his private chambers for a meeting. He kept us waiting for nearly an hour, while we stood at attention. Our kerchiefs hid the heads of those who had been shorn, though mine was never touched. I did not know why, but soon it would all come clear to me. I had been a fool thinking I had somehow escaped the sickness of the minds of our malevolent keepers. My education, the love given me in all my childhood, the self pride I felt for being who I am, my natural beauty, were all to be taken away from me. Before us stood that miserable small man who powered over us, and who was ready to show his manliness by striking us with his fists, or take the whip to us if his hand hurt. We were like frightened cattle about to be led to slaughter. But we were human beings, so we had a better understanding of what lay ahead of us. We simply did not know what it would really be.

"Meine Shatze!" This was a favorite expression of his, Shwarz, the small un-Aryan looking commandant, who thought of us as his treasure, his spoils of war.

"I have important men coming from Berlin, men highly decorated from the war, men who will inspect you laborers and report back to the Fuhrer." He puffed out his small chest as if he had spoken some great pronouncement, impressing on us how important this was.

"I want you women to be at your best behavior at all times, with showing very special respect for these very important officers. Understand?" We did not answer, for it might have been the wrong thing to do, so continued to stand at attention. The fat mouse continued.

"You are very lucky to be in my staff, because you are spared the hardships the other laborers must endure. I treat you well. I know the cook gives you extra food, and I turn a blind eye to this. But if you cross me, then I will punish him instead of you, for no infraction of the rules is forgotten. But I want you to be better than the others. This is war, and this is how it is. We have no choice in what happens to us, for the war must take precedence over all of us. So it is at great sacrifice to myself that I try to make your life easier here at the camp. Do not think this is easy for me. I am watched by other SS and Gestapo too. There is only so much I can do for you. But I do the best I can, and for this I hope you will help me."

A cold shudder went through us, because whenever a German SS asked for help, it was dangerous. One never knew if choosing to volunteer for anything asked by them meant an extra day of life, or the day of death. We had heard of the experiments performed on women by the doctors of the camp, and this was what we immediately imagined, that we had been selected for medical experiments. I had seen the results of these experiments, and it made my flesh crawl. Mostly they were Gypsy women and children, but it was horrible, to where the mind cannot accept it. Their skin had turned black, full of putrid sores, until their infections killed them. The commandant's request for help turned our hearts into cold fear.

"I am fond of you. You must understand, that I am about to ask you to help me. Now, I will speak with you individually. You may sit down where you can and relax. First I will call you," he pointed his finger at one of the new women who had arrived on the last transport. She still glowed with life, unlike those who had been here some months, now autumn turning into winter. She followed him into a side office. We soon could hear voices, more than one man's voice, and then after a longer time, we could hear the pleading of a woman's voice. Soon, she came out all red in the face and without looking at us went out of Shwarz's private chambers.

Women were called in one by one, until I was last. In each case, the result was the same, for shame was clearly written on their faces when they emerged. I wondered if Lyuba, who could not help herself smiling, would have had that smile as she exited now. No, she was the lucky one, I decided, in that she was not here. Then it was my turn.

"Come in," was the commandant's solicitous words. "This is major ... a name I no longer remember, who is to assist me in my selection." The major looked at me with cold eyes, but he nodded in acknowledgement to the commandant. I was not asked to speak, but told to listen carefully.

"You are last, because I am most fond of you. You work hard, you are clean, and your health is good. I do not know how to ask you this without embarrassing you, but the other women all understood what I am about to ask you." The major was undressing me with his eyes, showing some sign of life in them. "Would you please take off your work clothes?"

It was asked as a question, almost politely, but it was an order. I dared not refuse, though it had been a long time since I stood naked before a man. The last time was with my fiancée. I thought of him briefly, wondering what had happened to him, if he too was in some camp like this. He had been part of the resistance, both at the university and with partisans. I dared not think of him dead. Mikhail, I thought, save me.

I undressed without feeling, knowing that this is one more test of my humanity in hell. When my dress fell to the floor, I was totally nude, since they did not give us underwear, only socks for our feet.

"Take off your socks." The major spoke now, appearing interested in what he saw.

They both stood there examining me like some merchandise at the slave market, something to be sold or bartered, for a favor, for recognition in the eyes of some superior. It was no secret to me that I was to be a prize offered to some important man.

The major now approached me, and began looking at my pubic hairs which were still untouched, unlike those shaved off for other women.

"I told you," Shwarz said with pride. "I kept her special". The major nodded in agreement. His cold grey eyes studied me. He was a more or less handsome man, more Nordic looking, of athletic build.

"Put your hands against that table over there, and move your legs apart a little." The major was getting excited with these words. I was about to protest, fearing what they had in mind, when a voice in my head said to stay calm. I obeyed.

The major pulled out a cigarette from a silver case and began smoking it.

"Yes, I like her. This one will be reserved for Herr Himmler himself," he said with self satisfaction. "Would you mind if I spent some time alone with her?"

"No, not at all, bitte." With that the small commandant left the room.

When he had gone, the major began to unbutton his pants and taking them down. I turned in horror.

"No! You cannot!"

This stopped him short for an instant, already his hard penis showing beneath his military shirt.

"If you resist, you will be severely beaten," was his cold response. His heat did not go down. "Do not tell me you are virgin, like the other girls." He had a smirk on his face, a face I wanted at that moment to scratch with all my might. I froze, not knowing how to respond, when that same voice in my head said very calmly for me.

"If I am to be given to a very important man, he would not want soiled goods."

His leg muscles gave off a twitch, and he stopped advancing. It was as if something stopped in his heart pump, for his erection went down immediately. Fear. It was fear of a superior, that perhaps while I was in coitus with him, I might tell of the major. This stopped him. My face had grown hot and flushed, but my body trembled with cold. I looked over at my clothes on the floor. He followed my eyes, and then nodded. I immediately reached for them and hastily threw them over myself, and my socks, which I then stuffed into my wooden shoes. As I was about to leave the room, he reached over and touched my buttocks.

"You are a fine lass, young lady, a fine lass. An Aryan lass."

The fear and trembling did not leave me until I had gone back to my barracks and threw myself on the cold mattress in a flood of tears. I had come so close to being violated of my human being, so close to being fornicated into the last refuge of myself. My tears flowed until the call for formation was announced over the loud speakers, and I had to quickly rise, dry my face with the kerchief on my head, and make myself look normal again. But the fear had reached deep into my heart, and now I was afraid. But my fear did not make me weak. It made me strong.

I was ashamed, ashamed for what I had been subjected to. But I was more ashamed for the other women, because they were weak and succumbed to their fornicators. When I spoke with them again, I only very indirectly asked them what happened. Most would not say, afraid to talk about it. I asked Tania, the Romanian, who I knew was virgin.

"Are you still virgin?" Tears welled up in her eyes. "Shwarz?" She shook her head, and looked away.

How could that butcher of a man do this to such a fine woman? I felt the hatred in my heart turn cold, like the calm voice that told me what to do, what to say. And in that same calm way, I determined at that moment that I would do what I could to help these women. God help us, but we would not be used for the meat market again. I swore this so hard while standing at attention that I felt my nails bite into the flesh of my palms. I did not know how, but I swore to God I would do this.

4. Renato

I killed a rat today. I did not want to kill it, but it was hiding near where I hid my notebook. He might have gnawed on it, so I took off my wooden shoe and clubbed it to death. It was a wretch like me, lean and hungry, no doubt infested with fleas, no doubt a carrier of the black death. I did not feel a great pity for it, but killed it out of instinct, out of self preservation. In that notebook is all of my life, and I could not let it come to harm.

When the other prisoners came into the barracks, I had already skinned it, and since we were allowed a small fire in a metal bucket, as it was cold, I skewered it on a thin wire and had it roasting over the small flames. The smell filled the barracks, and if we had been discovered by the SS, we would have been punished for it. Cooking meat was not allowed in the barracks.

The capo, Jan, came in from work with the other men and asked what I was doing. So I showed him, and he smiled a wry smile.

"Mind if I have a taste? I have not had meat for many months, over a year."

This cheered the other men, who now also wanted a taste. There were sixty of us, so not enough to go around, so we decided to make a soup out of it, so all could enjoy the broth. But the meat would go to Jan and me, and a few morsels to some very weak prisoners who needed protein if they were to survive.

Now I was known at the men's barracks as the hunter. And all encouraged me to do it again. Snails had been eaten in the fields by nearly everyone, raw and fresh off the ground, wherever we could find them, though this too was punishable. The offense was a capital one, and anyone caught eating produce from the fields was summarily shot. I had seen a man hiding carrots in his trousers, until one fell out. The Slavic guard came over, made the mans stand before us all with his head down, and with one blow killed the man. We later learned he had done this before to smuggle them to a woman in the women's camp of whom he was fond. Another time a man was caught stuffing grass into his shirt. The German overseer came over to him on horseback and with one shot of his pistol killed him on the spot. Even a blade of grass was forbidden, for all belonged to the Reich, and we were not fit to eat it. The grass was for their livestock. Our food was several days old bread left over from the SS and guard's mess, with a thin spread of rancid smelling margarine, on some days, and the thin gruelly soup made of turnips. On good days we had lentils, and even more rare beans or a cooked bone, which at least gave some nourishment. The turnips were pig food, but most days this was all we got, and very thin at that, more like turnip broth. It was not enough to keep a working man fed, and though hunger gnawed at us daily, somehow we persevered. To not work was sure death, so with herculean strength we would rise every morning and by half past five in the morning arrange ourselves for our daily piece of bread. A thin warm dark liquid was offered later in the day, to torture us into thinking it was coffee, but this offered no nourishment except boiled water. Since we nearly all suffered from diarrhea, water was constantly needed to rehydrate, but not easily available. What water we got was given to us in buckets, it was unboiled, so the diarrhea never ended. So we should be excused for losing our humanity for a moment and relishing at the thought of eating a rat. With a few blades of grass thrown into the soup, it was nourishment.

We did not steal food from each other, which is surprising, but the Aryans had not yet reduced us to that. Nor was there cannibalism at the camp, though we had heard this happened in other camps. This was a working camp, and except for its usual brutality and killings, it ran almost normally. They had not yet taken everything away from us, for if they had, it would stop working and we simply would have accepted death. In our hearts, we all wanted to live, but when the spirit was lost, whether from punishment or ill health, or the loss of loved ones, we died. This would have been the case for Livia had Kostia not stepped in to help her. She said it was her doing to bring her to see her husband, and now it was again of necessity her doing to bring Livia back to life.

"Disziplin ist gut, mein Schönheit," I heard the officer say to one of the women. He was being kind to her, speaking in normal tones, not yelling as is commonly done. This SS man had developed a fondness for Slavic women, and was solicitous when his desire aroused him into humanity. The woman looked lost, not knowing how to take his advances. Then he would hold up a small piece of bread, and her heart would suddenly warm to the bait. If she had no other lover, or hope, she would give in to him, and be his mistress for a time, until he tired of her. You could tell which women had lovers, for they were slightly fatter than most. In spite of their wretchedness, some women, both Gentile and Jew, were quite beautiful. But it is more fair to say most women did not fall for this temptation. For those who did it meant an extra day of life with a little less suffering. But the consequence were as brutal. If they became with child, the children were taken away immediately, to never be seen again. If it was a fair and blond child, it might live in some orphanage somewhere, being half Aryan, to be added to the war fodder of the superior race. But if it was not, then it was killed immediately, sometimes before the new mother's eyes. This was a terrible price to pay for a piece of bread.

The Aryan devils had found that love was a tradable commodity. So they made sure that the men and women were separated, especially if they loved each other. Then it was easier to control them, with false promises of reunion, of a moment with their loved ones, even if only across a barbed wire fence. There had been stories of men and women so desperate to be together they would approach an electrified fence and grasp it, their fingers locked together in a final death grip, as their bodies convulsed from the electric shock. They were together for a brief moment before death. I had not seen this, but it was told. Most, however, did not resort to such desperation, but suffered quietly, nursing a hope in some far recess of their hearts, that they would be reunited someday.

This was the case with Livia, for she loved her Renato very deeply. So when a call went out that they needed volunteers to fix some machinery where I knew Renato had been sent, I volunteered. I then made my way with laundry to the officers' mess to find Kostia. She was not there at the time, and the orderly told me there was a meeting for the women. This was hard news, for I needed to see her, and I was about to leave when I heard hushed voices of the women returning to their work stations. I lingered, saw the capo woman, a strong ox of a woman named Svetlyana, barking orders at the women. They all looked dejected and ready to cry. When I had the chance, I quickly moved towards Kostia, when no one else was in sight, and grabbed her by the arm.

"What happened? Why are the women flushed and gloomy?"

I had pulled her into a broom closet and closed the door, so no one could hear us. We spoke in whispers.

"We were told Himmler will be here within a week. What are we to do? The girls are terrified."

She explained what they had been told they must do, and most were unwilling. I understood.

"Do they still menstruate?" I asked her. Knowing women who lose too much body fat cease menstruating, but I suspected these women were better kept.

"Yes, why?"

"Collect all their blood."

In the dark I saw her eyes grow wide with understanding.

"Then they could share it!" She almost burst out laughing with excitement.

"Yes. Pray there will be enough for all. It is a known fact that women menstruate with the moon, so if they are menstruating collect it, and keep it moist if you can."

"But it is unclean... Won't they get infections?"

"There is that danger, but there is no other choice. The German pigs are animals, but they still do not want their women unclean."

Kostia clapped her hands together once, from sheer excitement, when we heard footsteps approaching. We froze, she pressed against me as if we had become one. It was dark, but suddenly the door opened and light flooded in. We could feel a face looking in. It was Svetlyana. There was a tense moment when neither of us dared breathe. She held the door open a moment, like she was thinking of something, and then shut it with a slam. We both jumped, but did not let the other go. When silence had returned, we slowly unclamped our hold on each other. The danger was immense, had we been discovered, especially for me. For a dark skinned man to be found with the future concubine of Herr Himmler would have dealt me a most severe punishment. Kostia would have been made to cruelly suffer for this. I would have been killed.

Kostia got word to Livia that I was in search of her husband, and suddenly she began to speak again. Hope grew in her heart, and her daughter cried by her side. I had her explain that I could not be sure I would find him, but that I would try. If there was any miracle that I could get him back, I would. Livia fell to her knees in prayer.

When she saw me again, she kissed my hands and called me her Saviour. I lifted her head and said I am only a black man. I could promise no miracle.

When we got to our sister camp, we could not believe the horror. Word had gotten back how terrible conditions were here, but they could not be believed without seeing. When the truck brought us into the gate, a powerful smell of rotting humanity accosted us, we who were already hardened to camp life. In fact, the stench had made itself known even before we had arrived. Corpses were piled high at one side of the camp, before them were more corpses. The other corpses, those still living, were being put to work to dig the large mass grave into which they all would be tossed in. A gas chamber had been erected, with the mandatory crematorium to accommodate the dead. But this was a typhus epidemic, and those starved wretched human beings were dying from it. In this hell we pulled in and stopped.

"Schnell! Schnell!" the guards shouted at us. We could see from the turrets erected at intervals along the long barbed wire fence were machine guns pointing to us, as if we were going to escape, or start a revolution. It was madness, but the Ukrainian guards there were tense because of the typhus, and were as eager to pull the trigger to kill one more dying prisoner as keeping away from us. It meant nothing to them anyway, one more or less dead man. How these men would live with themselves through life if they survived this war was impossible to imagine for me. They should pray that they do not. The capos directed us towards the crematorium furnaces and put us to work to forge the parts necessary for its operation.

While working, I put out a clandestine word that I was looking for an Italian named Renato, who was an expert on fixing hinges for large metal doors. Later in the day, when we lined up for our very thin soup, even less filling than at our camp, for it had virtually nothing in it, I got word handed to me that Renato was still alive but ill with fever. This was bad news, I thought, and asked how I could see him. I was told his barracks had empty spaces, and I could stay there if needed. It was what I had hoped for.

Inside the dark barracks, as dusk approached, I found Renato. He was a mere skeleton of a man, perhaps handsome once, but now his face had the dark grey of a fever that had run its course, and he could barely lift it when I spoke his name.

"I pass word from your wife, Livia."

He looked up with confusion, his vacant eyes trying to find me in the dim light. I was surprised he had not been killed already, for he was too weak to work. But he was alive.

"She said to tell you, Ti Amo."

At that, the man raised himself on one elbow and began making an effort to sit up. I helped him raise upright, and he breathed out a long breath, as if he had been holding it in all this time. His face cracked a little, and his lips moved. "Ti amo..." he whispered. "Dove?" I knew Italian from my mother, so was able to speak to him easily. I explained how there were women in the camp who wanted to help his wife, and that I came to see if it was possible to bring him back. At this, he gained strength and sat upright with a new found vigor, the kind that men who are about to die will have.

"Did you eat?" I asked him. He shook his head. "Then here, take a small bite of this bread, only a small bite. I will go and see if I can find a way to bring you some soup. Live man, live! Your wife and daughter, they need you."

I had no idea how to find food in this God forsaken camp, but I inquired at where were eating the capos. In my pocket I had a small bar of soap I brought with me, currency in these horrific times, and showed it to the capo I judged to be more human than the others. He quickly put down his spoon and took me aside.

"What do you need?"

"I need a worker, a man who is in the barracks who is expert, and I cannot complete my task without his help."

"Which man?"

"I cannot give out names yet, but I can trade this soap for a bowl of soup, with potatoes in it."

He nodded, and took me back to the table, where he emptied his bowl into the one I brought with me. Renato would have a spoon. I then said, "and a piece of bread."

The capo broke his in half and gave it to me, which I quickly hid into my shirt. Then I gave him the bar of soap, which he also quickly hid in his shirt. Currency is currency, and if any others saw it, they would want it from him. This was the price of a small piece of soap, that a man's life may be spared.

I ran back as fast as I could to Renato, fearful that he would die before I got there. A guard shouted at me, and I explained I was from the other camp and wanted to return to my barracks before curfew, which he waved me on, calling me a son of a bitch. I nodded my head in submission and quickly moved on. My mission was not to be stopped by guards, or they may find more soap on me, so I hurried.

When I got back to Renato, he was still holding the bread, with maybe only two bites taken from it.

"Can you handle a little soup? It is still warm. And it has a potato in it."

The man took the bowl as if it were a chalice at communion and help it in his hands, and then slowly brought out his spoons from under his bedding, and began eating it like a child. Little bits of liquid dripped from his lips, as he had difficulty swallowing. Then another, and another. Soon he had the soup half eaten and he put the bowl down. With a skeletal arm he reached over to me and brought my head into his breast. There I stayed, quietly, while the man cried.

We abandon all hope where there is no one to bring us love. But the name of his wife, and the small food I brought him became his salvation for another day of life. We sat quietly together in the darkness without speaking, me chewing slowly on my bread, and he finishing the soup by carefully bringing each spoonful to his lips. By the time it was for me to find my place to sleep, all the others were already fainted dead from this world. Only us two were still awake, and Renato again took me into his arms, which already felt stronger on me. Before falling asleep, he quietly said to me, "Ti amo."

We completed the work assigned on the ovens, and with each day Renato gained more strength. His work was useful, though he clearly was no expert, but this was a ruse, so it did not matter. The capo who had helped me before became a sort of guarded friend, and after more bars of soap, I was able to convince him that we needed Renato at the other camp for more work. He was able to get me the signed papers for his transfer, glad to get rid of one more typhus ridden prisoner, and we all boarded the truck together. God help us, but now we were potential carriers of the disease, if not already infected. But my pulse was normal, and I did not suffer headaches, nor did the other prisoners who came with me. There was hope. When we drove through the gate, the corpses had already been thrown into the large pit, but new ones were being readied. We were glad to be rid of this place, and looked forward with anticipation to return to our own misery. It is better to be miserable where one knows, rather than dying in one that is unknown.

When we got back, I found a safe place for Renato in the laundry detail, so that he could recover his health. Jan helped me on this, for he was a good man. When I again had a chance to see Kostia, she gleefully told me the ruse worked. Himmler was disappointed, for he obviously liked her. I told her I had brought back Renato from the dead, and she clasped her arms around me with joy.

"Livia will be so happy! Oh, Giammai, you are a miracle maker. What a joy!"

Joy? I had forgotten what was joy.

That night in my barracks, after all had fallen asleep, I found my little book, especially well hidden this time beneath the floor boards. By the passing light of the guard tower, I wrote in my small print what had been with me all the way back from the other camp.

"There is no murder mystery here, for murder is what is normal, it happens daily. What is a mystery is why some of us live, and some of us die."

5. Herr Himmler

We lived in constant fear, a tiring exhausting fear, which anyone who had not experienced it would never understand. If I sound frantic in how I tell this story, it is only because that was how it was, that we were frantically, desperately, trying to survive. At any moment our life could end, and this was driven deep into our hearts in every waking moment, and even in our sleep. We lived in fear, and this fear was as much a mortal enemy as it was a salvation, for we had to survive, and the fear made us cautious.

Herr Himmler came with his delegation from Berlin to inspect our camps. We were told ours is a model camp of German efficiency, that we workers, they always called us worker and never prisoners, were well treated because of the good work done here. This was told to us as we had to stand at attention at the parade grounds, the women all dressed in their cleanest clothes. Warm coats had been given out to us, so that we could stand the winter cold, since it was winter, though these would be taken away later. The body learns to survive in the cold, feet frostbitten in our wooden shoes, trembling becoming a normal state, until we no longer noticed it. The speeches given I will not repeat here, for no doubt they are a matter of record and can be found. The message was the same, that if we do good work for the Fatherland, when the war is over, we will be rewarded with a normal life in the new Reich. These words sounded hollow to us, same as the warm coats were a lie. Himmler's coat was thick and spotlessly clean. Though he was not a big man, rather weak of chin, to us he looked like a god, while we wretched women stood hollow eyed, our spirit slowly draining from our bodies, cold and hungry, being given hope of a better life. It was a lie.

It was my war duty to the Reich to be Himmler's lover. How strange this seemed, like a monstrous paradox for the amusement of insane evil demons. How they must have laughed at what they had created. Where was God? I remember my mother and father praying quietly, since overt expression of religion was frowned upon in the new Soviet Ukraine, and me standing by them wondering what God they were praying to. Religion was superstition, we had been taught at school. Where was that God now? Where was the God of Love, the Creator who had made man in his image? What a monstrous joke it had all become. The only glimmer of God here was when someone touched you with kindness, and even that was accepted with fear, for it might mean that you had to surrender some part of yourself to accept it. It was dangerous to be kind, same as it was dangerous to accept kindness. This was the love that had been taken away from us. And in its place was put some perversion for the amusement of the SS officers, and for their top boss, Herr Himmler. It had fallen to me to be his concubine.

"Schnell, schnell, meine fraulein," the commandant ushered us quickly into a room together after the officers had been served their dinner. They were now talking loudly, smoking cigars and cigarettes, drinking in the next room. We were assembled for inspection, again told to look our best, for we were about to be honored by the great men of the Reich. Shwarz looked visibly nervous. This was a great moment for him to show off what he had so meticulously preserved for the enjoyment of the great heroes who were about to inspect us. If it all worked out well, he would be well reported to Berlin. If it failed, this could be a very bad mark against him. So he was nervous.

The officers were finished and now came in. They looked around, smiles on their red faces, for they had eaten and drunk much. We stood at attention as told, upright, chest out, feet planted firmly together, looking straight ahead. They filed before us, "shershun" they would say as they passed each one of us. They did not touch us, but looked into our faces and down out bodies, admiring and choosing what was theirs to have. We were their desert after a night of debauched dining. My heart turned cold as each one passed before me. Then Herr Himmler came and stood before me. I dared not look into his eyes. He mused a long moment, for he already knew I was his. "Uhumm", he said to himself, as if convincing himself that the selection was a good one. I was the meat he was promised, and it pleased him.

The capo Svetlyana was not in on our conspiracy, that we all had menstruation. But now it was time for me to reveal this to her, though I did not know how to do so. The commandant now addressed her.

"Are all the women clean?"

"Yes, mein Herr!" They had been bathed and made ready.

"Gut, gut..."

It was then that I overcame my fear and spoke out, in bad German.

"Mein Herr, if I may speak for the women?"

This caught them all by surprise, and there was a moment of silence as they tried to assess what was happening.

"What?!" the commandant shouted at me.

"May I say this to the capo, with your permission, for it is a sensitive matter."

He motioned that I move over to Svetlyana and speak with her, which I said very quietly when I faced her.

"The women are menstruating, my capo."

Her eyes grew wide, mixed with rage and fear, for she knew what this meant. It could be a punishment to her for not reporting this earlier. Now it would be a major embarrassment. She asked me if I was sure, since she was not menstruating. I raised my eyebrows, and shrugged, at great danger to myself, but had to make it look like it just happened.

The capo ox then took large steps and stood at attention before the commandant. In the yellow electric light of the room the air suddenly felt very hot and stuffy, like I would faint. But I held, as did the other women, trying not to tremble with fear.

She exchanged words in a quiet way, so that the commandant nodded without speaking. She came back to me.

"Are you sure?"

"I have seen their rags," I answered.

She nodded pensively and then returned to speak to the commandant. They exchanged words, and then she resumed her place at attention, satisfied that she was safe from further reprimand, since she had no power over the moon.

The commandant then turned to the officers, all of whom were busy talking amongst themselves, looking over our way from time to time.

"Gentlemen! We must find other ways to amuse ourselves this evening, since the moon has worked against us. The women are all dirty with blood."

This was met first with a stunned silence, and then they all burst out laughing. The men began pushing each other in boyish ways, saying that they moon was unlucky tonight. The women dared not blush, nor make a sound, for they were so frightened. We continued to stare straight ahead. One of the officers came over to the woman he had his eye on and touched her breasts, and then her ass.

"Very lovely, wie shun. Next time, I will take you next time."

The poor woman remained frozen in place.

Herr Himmler, being the top dog of the pack, did not do this, for he had to appear a gentleman, but his eyes looked me over once again. Then they all retired back to their dining room, with instructions to us to bring them more schnapps.

We were then dismissed, as the men began playing a phonograph with German marching songs, and cards were brought out. They did not want us around anymore, since we were dirty.

If the commandant was embarrassed by this episode, he did not show it. We were his currency, his wealth that he had built up, and we failed him. The next days our work loads increased, and the extra food from the kitchen ceased. In this subtle way, though we were not beaten, our punishment was being administered. This was only a warning, we knew, but it was one to be taken seriously. It would not happen again, for Svetlyana would make sure of it next time.

At the barracks, when the lights had gone out, all the women gathered around me, to thank me for saving them from doing what they did not want to. Each woman has her dignity, and though some would gladly give it away for a piece of bread, these women were not like that. It was not sex that was odious to them. We all like sex with the right man. It was the violation of their bodies against their will that was so horrible.

"It will not be easy next time," I warned them. "They will find a way to make us perform our assigned duty... or they will beat us into submission."

"How can we escape from it again?" one innocent looking child wanted to know.

"I don't know, my dear. I don't know. But God will help us."

I had almost begun believing that my words were the truth. It was a minor victory against these Nazi devils. We scored, for now. But I knew this too was a lie.

When Giammai came back from the other camp, and we had a chance to talk, he told me of how he had rescued Renato. I was so happy with joy, but we almost lost our lives for it. By chance the capo ox came into the room where she caught us talking, though it seemed she had not heard what was said.

"Back to work, you!" She pointed at Giammai, and to me, "It will be bad for you if I see you slacking again. Who gave you permission to talk to this prisoner?"

I did not answer but put my face aside, so she could strike it, which she did. Giammai left quietly with his bundle of dirty laundry without looking back. But in my heart I was glad, and the pain on my cheek felt good, for we had won again against these monsters. Livia will be so happy when she finds out her husband had been brought back from the death camp. I knew that this news would mean another day of life for her.

The typhus we all feared would come from the other camp did not happen. It was a miracle, because by all rights it should have, but it did not, not this time. The visiting delegation had left the next day, so we did not have to hear Himmler's speeches anymore. Our warm coats were taken away as expected, and we were once again forced to stand in the snow with our thin coats, all shivering and coughing. As I stood there in the cold, moving my feet in my socks to keep them from freezing, my mind set to wandering how we could deliver typhus infested lice to the officers's quarters. But there was no way to do this, since we would not know which lice had the disease, and since none came down with it here, we assumed that our lice were not infected. Still, it was a thought that kept me warm in the cold air. Funny to think that we had "our lice" and they had theirs...

As my mind wandered, all of us waiting for nothing in particular, since we all knew our work assignments and it was odd that the camp directors would waste so much time for nothing. Perhaps it was merely another way to dehumanize us, or perhaps some university educated doctor wrote some scientific paper on this, explaining how it is good to have the prisoners stand at attention for hours, as a way to make them rest. While stomachs rumbled from hunger, and some fainted, only to be beaten awake again by the capos circulating amongst us, I wondered what went through the minds of all of us standing there. I wondered what they thought of, of insanity as being normal, and sanity as being abnormal. Or were they even thinking at all? What hopes flickered in the hearts of those who had abandoned all hope?

I had hidden in my frock a piece of dark coarse bread I had stolen from the kitchen, I thought about it now. This I was going to take to Livia, so she could share it with her daughter. What could I do to make their lives here slightly easier? I do not know why they were important to me, but somehow I had adopted them as my own, my family that I did not have around me. Livia was not a young woman, fragile, and her daughter Gemma a lovely girl, large eyes that seemed to be always on the verge of tears. I wanted to help them, in the way Giammai helped them. Though they could see their other important human being only at a distance through a fence, it somehow helped them ease the burden of daily survival. Could I help others do this, I wondered? What can I do? What could any of us do? To help others seemed an impossibly monumental task, while standing at attention, feet freezing. Would I have swollen feet like the others? I moved my toes again, and I could still feel them. What a waste, I thought. What a waste of humanity.

It was then that I began to have an idea. We had heard that when Himmler departed, there were new instructions to build a large crematorium, under pretense that the bodies of the dead prisoners would be turned into ossuaries for their family members to reclaim and returned home for burial. They could get back the ashes for only three pfennig, saying the prisoner died of natural causes. Who knows who's ashes they would get, since many bodies would be burned together... another monumental lie. What absurdity, that "natural causes" should be inhumanity, brutality, starvation and exhaustion. But this was what was being said openly. What was not being said, but I knew this because Giammai told me, was that the prisoners would be gassed first at the sister camp, and then burned. In time, they might even build gas chambers here too, he said. We had heard the war was not going well for the Reich, and that Tommies had already bombed Hamburg, and the Americans Dresden, and some of the other camps. It was only a matter of time before they bombed Berlin, maybe even here, or so it was said. This was why they wanted to start the gas chambers, to eliminate the evidence of what they had been doing to the Jews, and to all those who might bring evidence against them after the war. It was bad. This was a very frightening idea to all of us, that they would kill us so that we could not talk. In the Aryan eyes, it was a worthy final solution to their problems. Make them make shoes and clothing, work them to death, and then kill them. Only a twisted mind could cook this. But they should never get away with it. I thought hard about this, and decided that the children must be the first to be saved from this burning holocaust, this sacrifice of innocent lives to their monstrous god. We had to somehow organize to protect the children. I looked around me at all the drab grey faces standing in the grey light, half frozen. There had to be a way.

6. A Day of Rest